The Return of the Son

By Robert Gottlieb

Only three months before Sergei Diaghilev’s death, in 1929, George Balanchine choreographed the final ballet created for the great impresario’s Ballets Russes.

It was The Prodigal Son (Le Fils Prodigue), a Biblical parable in three scenes. Balanchine was the house choreographer, only twenty-five years old – almost a nobody (despite his Apollo Musagète of the previous year), compared to the renown of the composer (Prokofiev) and the designer (Rouault); for Diaghilev, music and the visual elements always took precedence.

It was not a happy birthing. Prokofiev was rude and condescending; Rouault was grand and remote – and late. Balanchine would later say, “I could talk to Prokofiev, but he wouldn’t talk to me. Rouault never spoke. But in the middle of a rehearsal, he began balancing a chair on his nose.”

Balanchine felt that he was taken advantage of financially – and that this was due to Prokofiev’s greed. (He never worked with Prokofiev again.) And in any case, the center of attention was undoubtedly Serge Lifar, Diaghilev’s “protégé,” who had been the first Apollo a year earlier.

In 1950 Balanchine restaged “Prodigal” for the New York City Ballet, with the central character being performed by Jerome Robbins – a great performance. But then people of a later generation than mine aren’t aware of what a superb dancer Robbins was. And actor.

No one has ever surpassed the depth of feeling, the sense of degradation, he projected as – abandoned by his companions, stripped to his loincloth, eaten up and spat out by the pitiless Siren – he agonizingly crawled home to the family he had so furiously erupted out of.

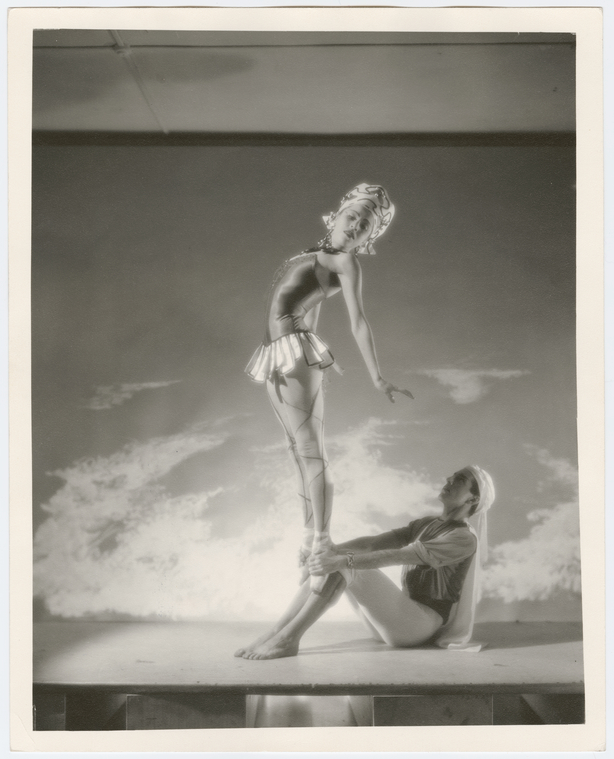

Later, and for many years, the role belonged to Edward Villella, our Founder. From the moment he burst out of the family’s tent in an amazing leap, he was galvanizing – the ultimate rebellious youngster, set on freedom and rejecting all constraint. But he’s also an innocent, and when he comes across the Siren with her nine horrifying “goons,” he’s an instant goner. She is the ultimate dominatrix, and he the ultimate victim. In their pas de deux she towers over him, straddles him, wraps her endless legs around, even sits on his head. She’s not even cruel, she’s inhuman. Villella often talked about the effect the beautiful, cool ballerina Diana Adams had on him as the Siren – he was terrified by her implacable iciness.

There have been many effective Prodigals and Sirens, and of course not only in Balanchine’s own company: Prodigal Son is performed around the world. Not only is it filled with thrilling stage effects – the fence that turns into a boat; the Siren’s cloak that billows out into the boat’s sail – but its final moments when the Prodigal returns and painfully clambers up into his father’s embrace, are as moving as anything in ballet. Balanchine was a great storyteller, and here the Bible provided him with a great – and universal – story.

Don’t miss the ultimate tale of sin and redemption:

Kravis Center: April 29 – May 1, 2022

Arsht Center: May 6 – 8

Broward Center: May 21 – 22

Photo credit: Alexander Peters in Prodigal Son. Photo © Gary James. Archival Photo credit: Courtesy New York Public Library. Maria Tallchief and Jerome Robbins in Prodigal Son. Choreography by George Balanchine. Photo © George Platt Lynes